When you hear the word "Druid" at least one of three things probably comes to mind: Old men in white cloaks, Stonehenge, or World of Warcraft. For this discussion, only two of those images are relevant, the wizened cloak-guys and Stonehenge; I'm sorry, but I'm not going to talk about the religion of WoW.

What I'd actually like to discuss is Druidry or Druidism, more specifically Neo-Druidy/ism. But before we jump into anything, let's get a little bit of history under our belts.

Who were the Druids?

Druids were mostly of Celtic heritage, whose lands and territories included Ireland, Scotland, England, Cornwall, Wales, the Isle of Man, and even into France, Germany, parts of Spain, and some Slavic countries. Generally, the Druids are connected with Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. Most of what is known about the Celts and Druids was recorded by the Romans, because the Celts did not have much in the way of a writing system, and therefore what's been written about them must be taken with a grain of salt because the Romans did not write without bias. The Druids are often credited with one of the oldest spiritual/religious (it's not absolutely clear whether they really had religion or not) groups, with a great connection to the Earth, Sun, Moon, and seasons, as well as seeming to have some belief in a sort of Mother Goddess. People often think that the Druids were the ones who built Stonehenge, but this has not been proven, and likely cannot be. They were split into three different groups: The Bards, who were poets and songwriters; the Ovates, who were "seers" and healers; and the Druids, who were the philosophers. Let me be clear, before we move on, that these people and their traditions are extinct because we really cannot know what they were like or what they did, but their bloodlines and inspiration goes on.

Ok, but who are these "Neo-Druids"?

Neo-Druidy/ism, which is often just called Druidy or Druidism, is a Neo-Pagan religion of relatively recent origins. You may have heard of other Neo-Pagan (which are often just called "Pagan" even if this use of the term isn't historically correct) religions such as Wicca, which is perhaps the most well-known and fast-growing of the Neo-Pagan religions, or one of the more esoteric paths which fueled Wicca, such as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Neither of these faiths are the same as Druidry (especially the Order of the Golden Dawn), but all share some similarities. Neo-Druidry can trace its roots back to the 1800s when a cultural movement was taking place in Britain which glorified the Celts and the historical peoples of Ireland and the UK with groups such as The Druid Circle of the Universal Bond rising up somewhere around 1909. In 1964, a man named Ross Nichols branched off from the previously mentioned group and formed another group called the Order of Bards, Ovates, and Druids (OBOD). He developed the group while collaborating with his good friend Gerald Gardener, who is often hailed as the "Father of Wicca." OBOD is still one of the most prominent Druidic groups in the world, closely followed by the American Druid group Ár nDraíocht Féin (ADF).

Neo-Druidy/ism, which is often just called Druidy or Druidism, is a Neo-Pagan religion of relatively recent origins. You may have heard of other Neo-Pagan (which are often just called "Pagan" even if this use of the term isn't historically correct) religions such as Wicca, which is perhaps the most well-known and fast-growing of the Neo-Pagan religions, or one of the more esoteric paths which fueled Wicca, such as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Neither of these faiths are the same as Druidry (especially the Order of the Golden Dawn), but all share some similarities. Neo-Druidry can trace its roots back to the 1800s when a cultural movement was taking place in Britain which glorified the Celts and the historical peoples of Ireland and the UK with groups such as The Druid Circle of the Universal Bond rising up somewhere around 1909. In 1964, a man named Ross Nichols branched off from the previously mentioned group and formed another group called the Order of Bards, Ovates, and Druids (OBOD). He developed the group while collaborating with his good friend Gerald Gardener, who is often hailed as the "Father of Wicca." OBOD is still one of the most prominent Druidic groups in the world, closely followed by the American Druid group Ár nDraíocht Féin (ADF).Druidry is an Nature-based faith and has been described as, "a group of religions, philosophies and ways of live, rooted in ancient soil yet reaching for the stars." (ADF website). Many people describe Druidry as a religion, while others say that it is a way of life, or a philosophy which they incorporate into their own religious practices and spiritual beliefs. For example, there are plenty of Buddhist, Christian, and Jewish Druids.

I realise that this is just a bunch of history and not much about what the Druids really believe or do, but I hope that through the analyzation of a few prominent markers of Druidry, I will be able to show you what they believe.

Symbols

That being said, I've chosen a very things about Druidry which I think make up it's essence as I understand it. These symbols of Druidry are as follows:

- Reverence of Nature

- The Three Realms and the Afterlife

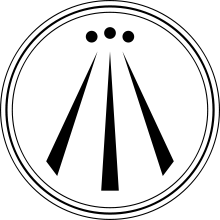

- The Awen

- The Wheel of the Year

And with that, let us move on to our next topic: The Druids' reverence of Nature!